A new standard classification system of rosacea, developed by a consensus committee from the National Rosacea Society (NRS) and review panel of 28 rosacea experts worldwide, has been published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (November 1, 2017). “There has been an explosion of research on rosacea since the first standard classification system appeared in 2002, and that has resulted in a much deeper scientific understanding of this common but once little-known disorder,” said Richard Gallo, MD, chairman of dermatology at the University of California-San Diego and chairman of the NRS consensus committee.

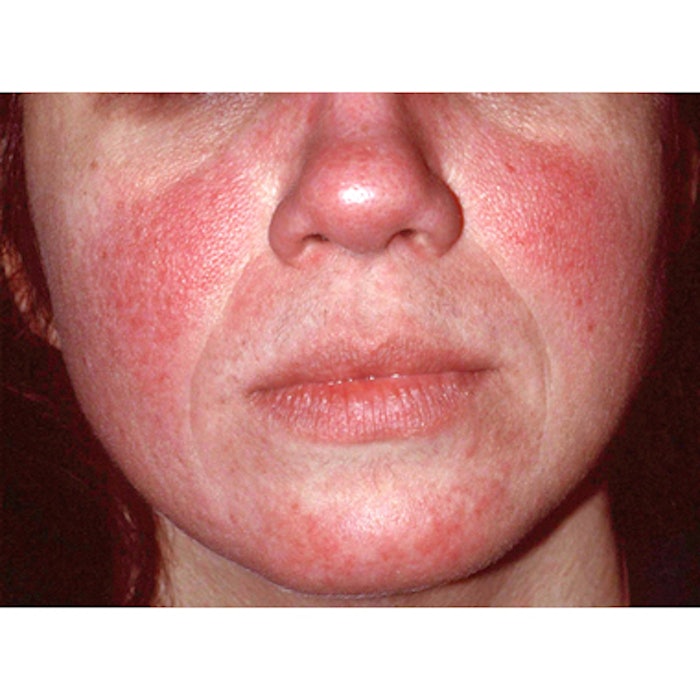

While the original classification system designated the most common groupings of primary and secondary features as subtypes, the committee determined that because rosacea appears to encompass a consistent inflammatory continuum, it now seems appropriate to focus on the individual characteristics, called phenotypes, that may result from this disease process. Using the new system, the presence of one of two phenotypes—persistent redness of the facial skin or, less commonly, phymatous changes where the facial skin thickens—is considered diagnostic of rosacea. Additional major cutaneous signs or phenotypes—which often appear with the diagnostic features—include papules and pustules, flushing, telangiectasia and certain ocular manifestations. The presence of two or more major phenotypes independent of the diagnostic features is also considered diagnostic of rosacea. Secondary phenotypes, which must appear with one or more diagnostic or major phenotypes, include burning or stinging, swelling and dry appearance.

In ocular rosacea, suggestive signs noted by the committee include telangiectases on the eyelid margin and bloodshot eyes, as well as inflammation and growth of fibrous tissue on the eye. Burning, stinging, light sensitivity and the sensation of a foreign object may also occur, as well as conjunctivitis, inflammation of oil glands at the rim of the eyelids (blepharitis) and crusty accumulations at the base of the eyelashes, in addition to others.

“Although rosacea’s various phenotypes may appear in different combinations and at different times, research suggests that all are manifestations of the same underlying disease process, and that rosacea may progress not only in severity but to include additional phenotypes,” said Dr. Gallo.

The committee also acknowledged the psychosocial effects of rosacea, noting that multiple patient surveys have documented rosacea’s substantial adverse impact on emotional, social and occupational well-being. They stressed that this should also be an important consideration, and suggested the development of appropriate severity scales to measure this dimension, as well as the need for further research to adequately assess rosacea’s negative effects.

Additional areas for future research recommended by the committee include: the prevalence of rosacea in individuals with darker skin types; genetic factors that might affect the disease and may also be used to identify potential further comorbidities; the role of the skin microbiome in rosacea; and associations between rosacea and increased risk for a growing number of potentially serious systemic disorders.

In addition to Dr. Gallo, the consensus committee included Richard Granstein, MD, chairman of dermatology at Weill Cornell Medical College; Sewon Kang, MD, chairman of dermatology at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; Mark Mannis, MD, chairman of ophthalmology at the University of California-Davis; Martin Steinhoff, MD, chairman of dermatology, Qatar University and director of the University College Dublin Charles Institute of Dermatology; Jerry Tan, MD, adjunct professor of dermatology at the University of Western Ontario; and Diane Thiboutot, MD, professor of dermatology and vice-chair for research at the Pennsylvania State University.

Image courtesy of the National Rosacea Society